I got a call from a journalist yesterday asking me if a recent claim that a pint could cost £20 (in London, by next year) was accurate. It prompted me to check our figures both in the bar and the brewery.

Keeping abreast of rising costs is simultaneously one of the most important and the most depressing things you can do in business.

At the beginning of each year we look at our costs and how many times we think we’re going to brew in the year. Doing this gives you an idea of the costs you face and guides you to the amount you need to charge to cover those costs.

I spent the morning (my day off as it happens) playing around with spreadsheets partly to get my head round the cost increases we’ve had during the year and partly, if I’m brutally honest, because I quite like playing around with spreadsheets.

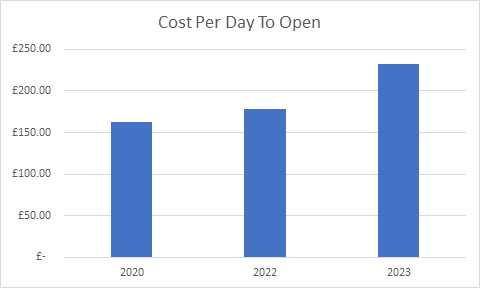

I started out by working out what we’d need to charge per pint in 2023 to cover the increased cost of opening the bar every day or, alternatively, how many more pints per day we’d have to sell without putting the price up to cover that cost (I should point out at this juncture that we didn’t bother doing this exercise in 2021 because we were closed). Sound interesting? Then strap yourself in, we’re going on a ride.

Obviously, we’re lucky enough to have a bar and a brewery so we have a handle on the running costs of both sides of the business. So, let’s start with an analysis of how we cost a keg of our Mighty Stout.

We start by adding up all our overheads; rent, electricity, water, insurance, staff costs, vehicle costs to get an amount and we then divide that by the number of brews we think we’re going to brew the following year. This gives us a per brew overhead. We then add the variables; ingredients, duty rate and brewlength which gives us a cost per litre then we add the container (cask/keg/can) cost to give us a cost price.

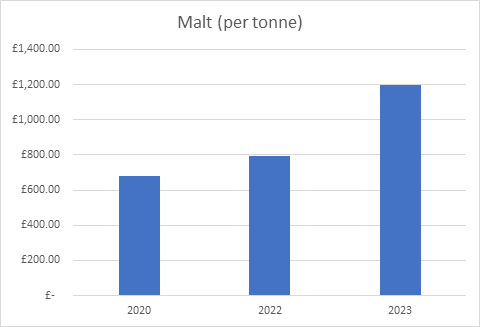

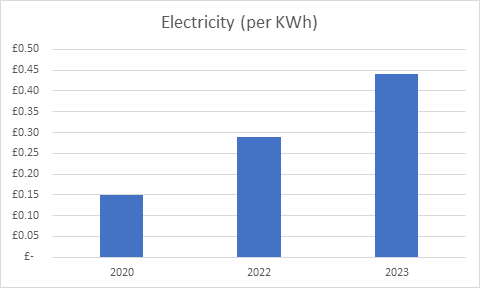

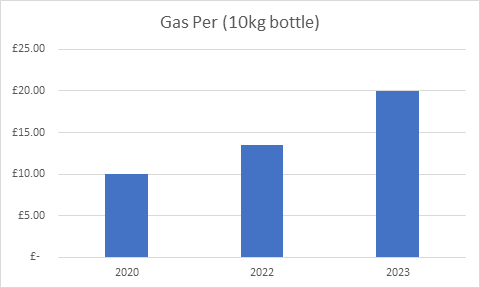

The main costs that have changed over the last two years (or which are about to change) are base malt, electricity and CO2. So let’s take a look at those.

I was paying £680 a tonne for pale malt in 2020 and £793 in 2022. Other brewers I’ve been talking to have been quoted between £1000 and £1200 for 2023. We’ll know nearer the time.

Now the big one, electricity. We have different suppliers for the bar and the brewery. I was paying 15p per KWh in 2020, this year it went up to 29p until July whereupon it went up to 43p where it will stay until next June.

Lastly CO2 which is a by-product of fertiliser manufacture. Last week we heard that one of the two factories which produce fertiliser is shutting down because the power cost is currently too high to continue production. This will obviously cause a shortage which will impact on price. We think this will translate to £20 per 10kg bottle and it will affect both bars and breweries.

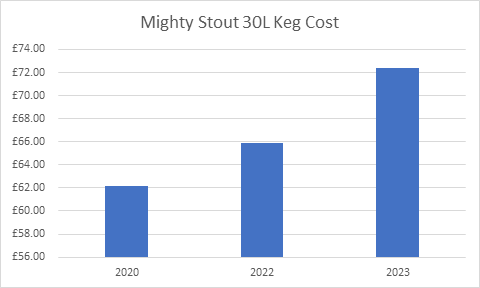

Here’s the impact this has had on the cost price of a 30L keg of our Mighty Stout with a projection of the price for 2023.

So, the beer that, two years ago, cost us £62.14 a keg to produce now costs £65.93 and will cost £72.37 if we’ve got those costs right.

What does that mean for the pubs who need to sell it, then?

In the same way as we work out what the overhead is in the brewhouse, we do the same in the bar. Add all the costs up, rent, electricity, insurance, water, rent, staff costs and then divide them by every day you’re open.

This gives you a “break even” figure to hit before we can even think about making a profit. We’re open four days a week plus a few bank holidays and Christmas so let’s say 220 days per year.

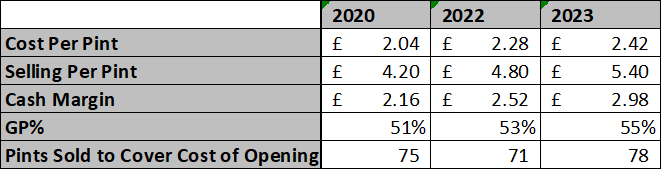

The problem here is that the cost of the product into the bar has gone up but so have the bar’s overheads. So, if all we sold was Mighty Stout (obviously we don’t but bear with us for now) we would have to price it accordingly to sell a similar number of pints in each corresponding year.

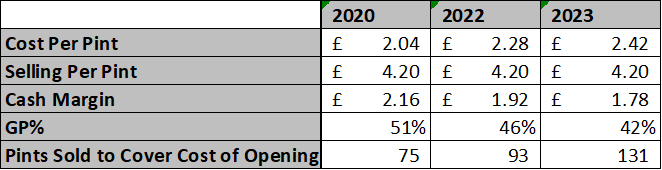

Or, to put it another way, these are the number of pints we’d have to sell each day that we opened if we chose to keep the price the same. Remember this is simply to cover our costs. Our margins are slightly better than this because the brewery doesn’t have to charge the bar VAT but it does give you an idea of the relationship between a normal bar and brewery.

Of course, none of this makes a blind bit of difference if the squeeze on domestic gas and electricity prices on the drinker means they can’t even afford £4.20 a pint.